Male and female bodies are very different, but new research from DMCBH member Dr. Liisa Galea’s lab found not many studies are taking these differences into account. The paper was recently published in Nature Communications.

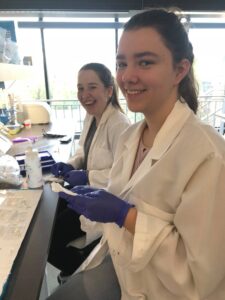

We spoke to lead authors Rebecca Rechlin—a research assistant in the Galea lab—and undergraduate student Tallinn Splinter to learn more about sex differences in the literature.

What were the main findings of this analysis?

Rebecca: We looked at over 3,000 neuroscience and psychiatry studies from 2009 to 2019 and found only 53 per cent of these studies actually included both males and females, and only 19 per cent used an equal number of males and females throughout their study. Only 5 per cent of papers analyzed sex as a discovery variable, meaning the rest of the papers didn’t use sex as a factor in their analysis.

What prompted you to do this study?

Rebecca: We’d been thinking about this for a while because we noticed there was a lack of studies that focused on sex differences, so we wanted to quantify this by doing an analysis. The pandemic gave us the opportunity to do so since we couldn’t be in the lab. Tallinn and I were actually roommates at the time, so we’d both be in our rooms looking over all of these papers.

Tallinn Splinter (front) and Rebecca Rechlin

Why is it important to consider sex differences in neuroscience?

Tallinn: If we don’t look for any differences, we won’t find any, even if they do exist. There are many neurological diseases where the symptoms are different in males compared to females, and sometimes treatment works for one sex but not the other, so we really need to be analyzing for potential differences.

How should researchers do this?

Tallinn: For starters, researchers need to actually analyze data by using sex as a factor. They also need to use a balanced and consistent study design, meaning they need to use both males and females consistently and in relatively equal numbers. And even if they don’t find any sex differences, then the paper should make that statement with supporting statistics and a table to show the means and variation of the dependent variables by sex.

What got you both interested in neuroscience?

Rebecca: The first year of my undergraduate program I worked in a lab and that’s what really sparked my interest. Once I chose behavioural neuroscience as my major as I was able to take more specialized courses which kept me excited about the field.

Tallinn: I’ve always been interested in neuroscience, especially Alzheimer’s disease and depression. When I got the opportunity to work in a lab, it confirmed that this was the subject area I wanted to focus on.

Dr. Liisa Galea

What do you enjoy most about being part of the DMCBH community?

Rebecca: The Galea lab is so supportive and it’s been really fun having the opportunity to collaborate with other labs. I also like going to seminars and hearing about ongoing neuroscience research.

Tallinn: The people and the community are what I enjoy the most. I’ve also had unique opportunities to volunteer, for example I participated in the Women’s Health Research Cluster podcast.